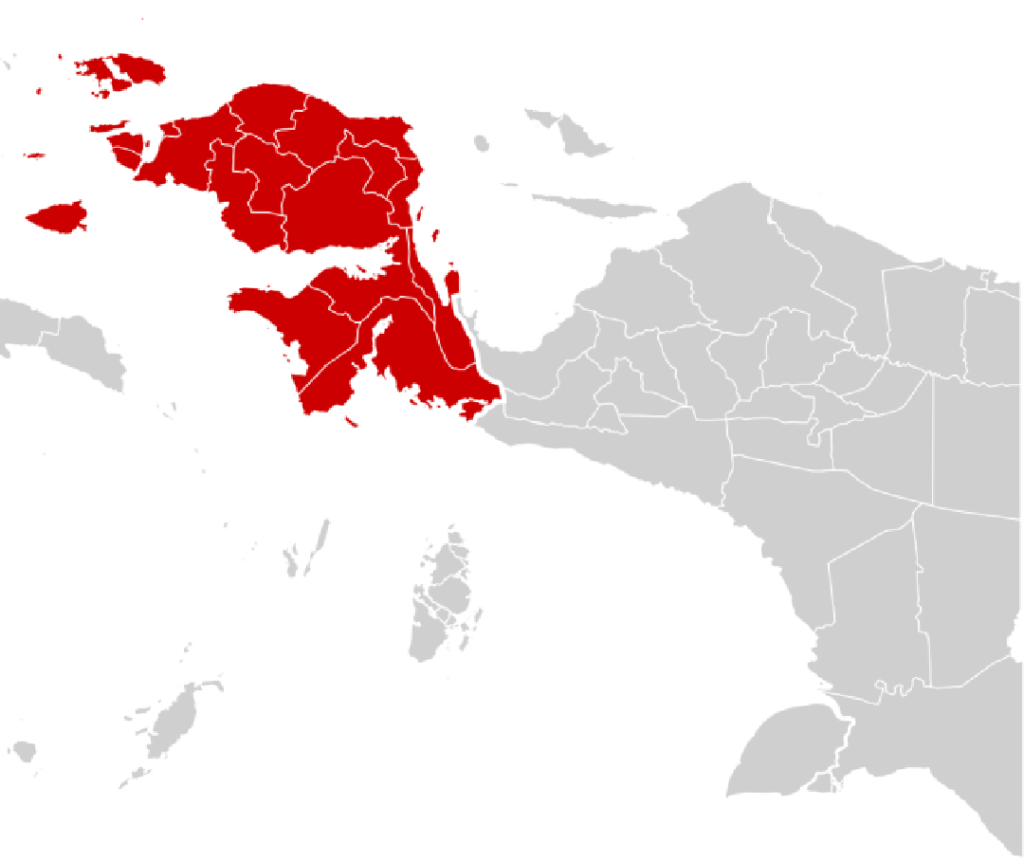

The sprawling highlands of Central Papua have long been known as a crucible of mineral wealth. Beneath the rugged terrain near Mimika, some of the largest deposits of copper and gold on the planet are still being uncovered and prepared for extraction. The new frontier in this geologic treasure hunt is the so-called Kucing Liar deposit, a mining zone that has captured the attention of economists, engineers, and policymakers alike because of its size and the prospects it holds for both PT Freeport Indonesia (PTFI) and the Papuan communities in whose land this wealth lies.

This narrative is not only about geology and corporate strategy but also about how mineral riches, often buried deep beneath mountains, can become a catalyst for economic growth and shared prosperity if managed with foresight, fairness, and cooperation among local and national stakeholders.

Kucing Liar: A New Chapter in Mining

The operations of PT Freeport Indonesia in Papua are renowned for their immense scale and enduring presence, centered on the Grasberg mine, a site housing one of the planet’s most valuable mineral deposits. Long before the first ore left Grasberg in the 1970s, however, prospectors had already pinpointed promising locations within the highlands. A particularly appealing target, known informally as Kucing Liar, is now transitioning from geological study to the production planning stage.

Recent exploration data suggests the Kucing Liar deposit holds roughly 8 million ounces of gold and around 8 billion pounds of copper in reserves that can be extracted. These numbers reflect a considerable upward revision from previous assessments, partly a result of more comprehensive feasibility studies and advancements in modeling.

The scale of these reserves positions Kucing Liar among the world’s most significant yet-to-be-developed mineral assets.

If it reaches full production capacity, analysts believe it could yield hundreds of millions of pounds of copper and hundreds of thousands of ounces of gold each year for decades, providing a sustained flow of materials that are critical to global industries such as renewable energy, electronics, and infrastructure.

Originally, Freeport had targeted a 2030 commercial start date for the Kucing Liar mine, following years of preparatory development and investment in underground infrastructure. This timeline reflects the technical complexity of converting a prospective deposit into a producing mine, particularly in the challenging terrain of the Papua highlands.

A Strategic Turn Toward Underground Mining

Freeport’s transition from open-pit mining to underground operations is not new, but it gains fresh urgency with Kucing Liar. Much of the Grasberg site has already shifted underground, with major operations such as Grasberg Block Cave and Deep Mill Level Zone producing substantial quantities of copper and gold. Kucing Liar is intended to build upon this strategic emphasis.

From a practical standpoint, underground mining at Kucing Liar will necessitate intricate tunneling, ongoing rock face reinforcement, and the incorporation of advanced ventilation and ore transport systems. These elements represent some of the most capital-intensive facets of mining, demanding substantial initial financial outlays. Industry projections indicate that the Kucing Liar development will necessitate hundreds of millions of dollars in annual capital expenditures over several years to establish infrastructure and expand drilling operations.

The rationale behind Freeport’s commitment to this technically challenging methodology is clear: the mine’s long-term operational lifespan and its economic sustainability are contingent upon it. Open-pit mining, although providing quicker returns in the initial years, is unable to access the deepest and most concentrated ore deposits without causing considerable environmental harm.

Underground mining, though more expensive per ton of ore extracted, allows companies to reach these reserves with a smaller physical footprint and superior long-term yields.

Divestment Strategy and Local Ownership

Yet for all its geological promise, the Kucing Liar project’s real significance to Papua lies not just in the metals it will produce but in the opportunities it presents for Indonesian and Papuan stakeholders to secure a greater share of the benefits.

In 2018, Indonesia secured majority control of PT Freeport Indonesia by increasing government ownership to 51.23 percent through state-owned enterprises, with a specific 10 percent stake reserved for Papua’s regional governments as part of a broader agreement. Under this arrangement, shares are distributed to local government entities and managed through regional companies to ensure that a meaningful portion of mining profits stay within the province.

Building on that foundation, Indonesian policymakers are now advancing plans to increase the government’s stake further, with discussions underway to complete a divestment process in 2026 that could raise Indonesian ownership by an additional share portion. While some reports throw around numbers like 12 percent for this new divestment phase, local leaders are laser-focused on making sure Papua’s share, starting with that initial 10 percent, actually translates into real economic gains for the people living there.

This isn’t just a token move. Holding a stake in a big mining company like Freeport means getting dividends, having a say in how things are voted on, and influencing how profits get reinvested. For Papua, the proceeds could mean money for schools, hospitals, roads, and other public services that have often been starved of resources.

Connecting Mineral Wealth to Community Well-Being

For years, Papua’s natural resources have fueled global markets, while many communities in the area have seen only modest improvements in their quality of life.

Mining towns experienced expansion, but rural regions outside the mining zones frequently saw less progress. This disparity has fueled discontent regarding the equitable distribution of mining-derived advantages.

In response, both local and national authorities are advocating for structures that link revenues from extraction activities to wider developmental objectives. The transfer of mining shares to Papua serves as a prime example of such a mechanism. By reinvesting mining profits into public services, the entire region can reap the benefits of the resources that contribute to its significance in the global market.

Furthermore, there is an increasing focus on employment training and the inclusion of local workers in technical and managerial positions.

Cultivating the skills of Papuan workers in fields like mining, engineering, logistics, and environmental management is key to developing the region’s human capital. This, in turn, will help Papua move toward a more diverse economy, one that isn’t solely reliant on mining.

Moreover, there’s ongoing debate about how to distribute the profits fairly from mining across Papua’s various provinces. Local governors are actively discussing with government ministries ways to ensure that the benefits of Freeport’s shares are shared throughout the region, rather than concentrated in just one area.

However, these projects, such as Kucing Liar, aren’t without their problems. Underground mining presents its set of dangers, including potential geological instability and environmental damage if not properly controlled.

Water pollution and the destruction of natural habitats continue to plague mining areas globally.

In Papua, where the ecosystems are both rich in species and delicate, it’s vital to find a way to develop the economy while also protecting the environment. Freeport and the Indonesian government have both stressed their dedication to responsible mining, pointing to monitoring programs and environmental management plans that meet national standards.

However, critics, including environmental groups and civil society organizations, believe that mining needs to be heavily regulated to prevent lasting damage to the environment. They advocate for transparent reporting, independent assessments of environmental effects, and real community consent processes that give local people a say in how their land is used.

These perspectives are crucial as Papua approaches a new era of mineral development.

A Vision for Shared Growth

The Kucing Liar project represents a crossroads of extraction and equity. It demonstrates how contemporary mining, when combined with strategic divestment and local ownership, could potentially further regional development objectives. Yet, achieving this objective will require cooperation between Freeport, the Indonesian government, and Papuan authorities to guarantee that the generated revenue benefits the communities that provide the resources.

For many Papuans, the dream is that mining profits will finally translate into tangible benefits: better education, improved services, and opportunities that have long felt unattainable. The narrative surrounding Papua’s mineral wealth has frequently focused on exports and foreign investment. Now, with the Kucing Liar project and the divestment plans taking shape, the story is evolving to include local involvement and shared gains.

The next ten years could mark a significant shift as PTFI prepares for expanded development and the government finalizes its divestment strategy. If handled fairly, the mineral wealth of Kucing Liar could help create a future where Papua’s economic advancement is built not just on the resources extracted, but also on the well-being and aspirations of its people.