On February 20, 2026, in Nabire, the capital of Papua Tengah (Central Papua) Province, Governor Meki Nawipa stood in front of reporters and community leaders and gave a speech that was both very personal and very political. He wasn’t talking about roads, mining permits, or changing the government. He was talking about kids. About families. He also talked about what will happen to Indigenous Papuan (Orang Asli Papua) in the future.

People first started talking about the idea seriously in August 2025. Governor Nawipa said that the Papua Tengah provincial government was getting ready to start a free in vitro fertilization program, or IVF, to help Indigenous Papuan couples who have trouble getting pregnant. He said the goal was to help protect the long-term population growth of Orang Asli Papua, or OAP for short.

The proposal seemed bold to a lot of people in the room. For some, it was emotional. For some, it felt like it had been too long.

A Worry About Demographics

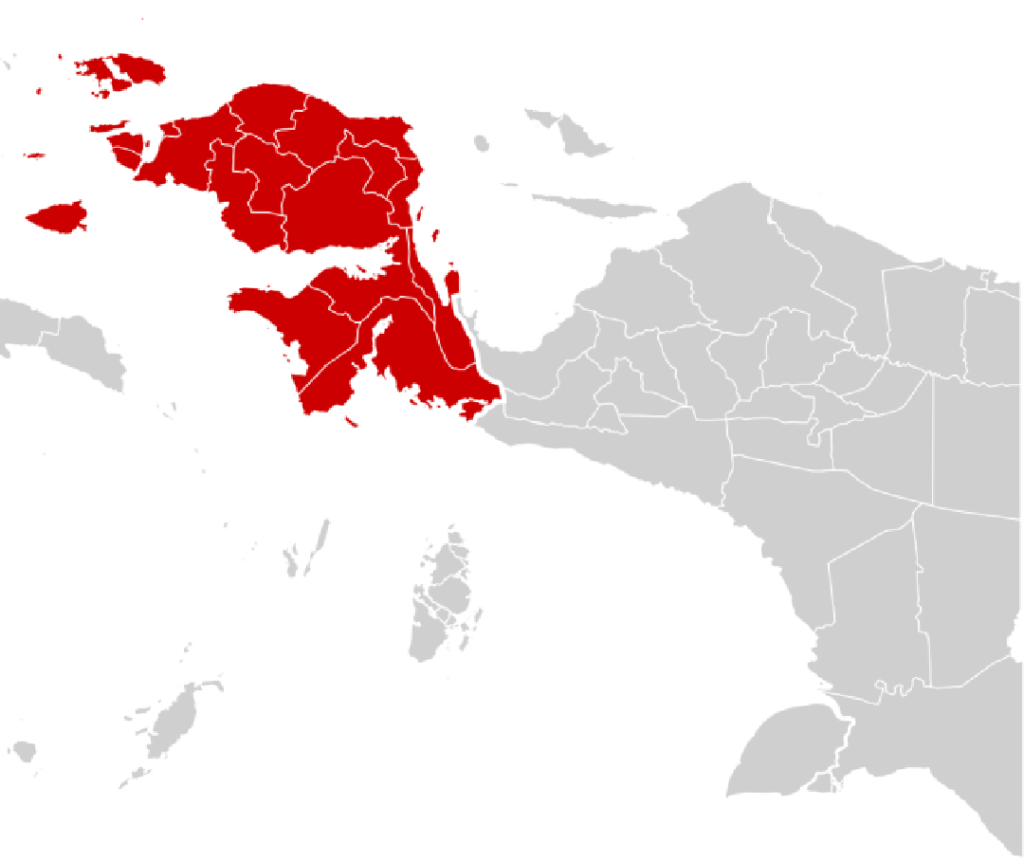

Papua Tengah is one of Indonesia’s newest provinces. It was officially created in 2022. There are many different types of people living in the province, but at its heart are Indigenous Papuan communities with deep cultural roots.

According to information released in August 2025, there were about 526,410 Orang Asli Papua living in Papua Tengah. Provincial officials, including Deputy Governor Deinas Geley, made that number public. He stressed how important it was to quickly classify OAP communities and give them policy support.

On August 10, 2025, Deputy Governor Geley said that the provincial government needed to quickly agree on a clear classification of Orang Asli Papua so that policy programs can really help the people they are meant to help. He stressed how important it is to take population sustainability seriously, especially in areas where the population is changing.

Governor Nawipa agreed with those worries. He said in a speech that was reported on in mid-August 2025 that keeping the cultural and social continuity of Indigenous Papuans needs more than just symbolic actions. It needs real policy changes.

He said that one of those interventions could be giving families who really want children but can’t have them because of health problems access to reproductive health technology.

The Human Side of Not Being Able to Have Kids

There are very personal stories behind the numbers.

Some couples quietly deal with the pain of infertility in both rural highland villages and urban neighborhoods. Having kids is not only a personal choice in traditional communities; it is also a social norm. Children have clan names, get land, and carry on their ancestors’ lines.

The weight can be heavy for couples who can’t have children. Some people feel social pressure. Some people are going through emotional pain but don’t talk about it.

When Governor Nawipa brought up the IVF plan, he was aware of this fact. He didn’t just see it as a way to reach more people. He said it was a matter of caring.

He said, “There are a lot of OAP couples who want kids but can’t have them because of health issues.” “The government needs to be there to help.”

In vitro fertilization (IVF) lets eggs and sperm come together outside the body and then be put into the uterus. IVF is common in big Indonesian cities like Jakarta and Surabaya, but it is still too expensive and hard to get for families who live in remote areas.

The price alone makes it out of reach for most families in Papua Tengah.

So, the idea of giving away IVF for free is very important.

A Program With a Clear Goal

Governor Nawipa said in August 2025 that the free IVF program would only be available to Orang Asli Papua couples who meet medical requirements and choose to have the procedure. He stressed that the government’s goal is not to force people to do things or change society, but to help.

He said that participation would depend on a medical evaluation and informed consent. The project would be carried out with care, following ethical standards and professional supervision.

Deinas Geley, the Deputy Governor, also stressed the need to make health services more ready. He said that the province needs to improve its healthcare system and make sure that there are enough qualified specialists available before starting such a program.

The provincial government does not want this proposal to be the only one. It is part of a larger plan to make maternal and child health services better, make clinics more accessible, and raise public awareness of reproductive health.

Responses from the Community

The news of the plan spread throughout Papua Tengah, and people had a wide range of strong reactions.

Some church leaders in Nabire said they were cautiously in favor. They liked the idea of making families stronger, but they said to be careful when talking to religious and traditional leaders. For a lot of Indigenous Papuans, having children is closely linked to their spiritual and cultural beliefs.

People in remote villages talked around cooking fires and in community halls. Some older people thought the initiative showed that the government is thinking about the long-term survival of Indigenous communities.

A young woman in Nabire, who had been married for six years and had no children, said that hearing about the program gave her a lot of hope. She and her husband had thought about going to Java for fertility treatment, but they couldn’t afford it. The thought that the province might help made them feel like their struggle was being recognized.

Some people also asked practical questions at the same time. Would the program take money away from other important health needs? Would rural clinics be able to do such complicated procedures? Would people respect traditional values?

These questions show that people are having a healthy conversation instead of just saying no.

Capacity and Implementation in Healthcare

It takes more than a political announcement to start a free IVF program. It needs trained professionals, labs, medicine supply chains, and long-term follow-up with patients.

Health officials from the provinces have started checking hospitals and clinics in Papua Tengah to see if they are ready. We are looking into forming partnerships with national referral hospitals and experts in reproductive health.

Governor Nawipa has said that it will take time to build capacity. He has said that the program will be rolled out slowly and carefully, with safety and openness as the top priorities.

The provincial government also wants to include people from the community in making rules about who can get help and how to get it.

A Broader Strategy for Demographics

For a long time, people have been keeping a close eye on demographic changes in Papua. Population composition has been affected by migration patterns, economic growth, and urban growth.

Many Indigenous leaders think that keeping a strong OAP population is important for keeping cultural identity and social stability.

This larger demographic picture is what the free IVF program is based on. It is not shown as a way to deal with a crisis, but as a way to help families who want to have children.

Governor Nawipa has said many times that cultural survival isn’t just about keeping traditions alive; it’s also about giving communities modern tools when they need them.

Finding a balance between modern medicine and tradition

The intersection of modern reproductive technology and traditional beliefs is one of the most sensitive parts of the IVF conversation.

In many Papuan communities, giving birth has religious and spiritual meaning. Elders and religious leaders often bless pregnant women and newborns.

The provincial government has started talking to traditional leaders, religious groups, and women’s groups because they know this. The goal is to make sure that the program honors local customs and doesn’t cause any confusion.

A respected elder in Nabire said that modern medicine and tradition don’t have to be at odds with each other. He said, “Our ancestors used the information they had.” “We have learned something new today. The important thing is that we use it wisely.

A Plan for the Future

The IVF proposal is mostly about the future.

Governor Nawipa has said that he wants Indigenous Papuan kids to grow up healthy, educated, and proud of who they are. He thinks that social resilience and population sustainability are linked.

For families who are having trouble getting pregnant, the chance of getting government-funded treatment gives them hope that their family line can continue.

For the province, it shows that they are willing to try new things in health policy while also taking into account the specific needs of the area.

Conclusion

The idea of starting a free IVF program in Papua Tengah has led to one of the most important public discussions the province has had in a long time. It talks about culture, health, identity, and the deep human need for family.

Governor Meki Nawipa’s plan is part of a larger effort to help Orang Asli Papua in many ways, not just through building roads and businesses, but also in more personal ways.

As the policy goes from being talked about to possibly being put into action, it will be important to plan carefully, get the community involved, and make sure that ethical safeguards are in place.

The human aspect is what stands out the most right now. Couples who have long wanted kids feel like they are being seen. Elders feel like they are being listened to. Leaders are being honest about how to keep the population stable.

The talk in Papua Tengah is no longer vague. It’s about real families, real hopes, and the quiet resolve to make sure that the next generation of Orang Asli Papua grows strong on their ancestral land.