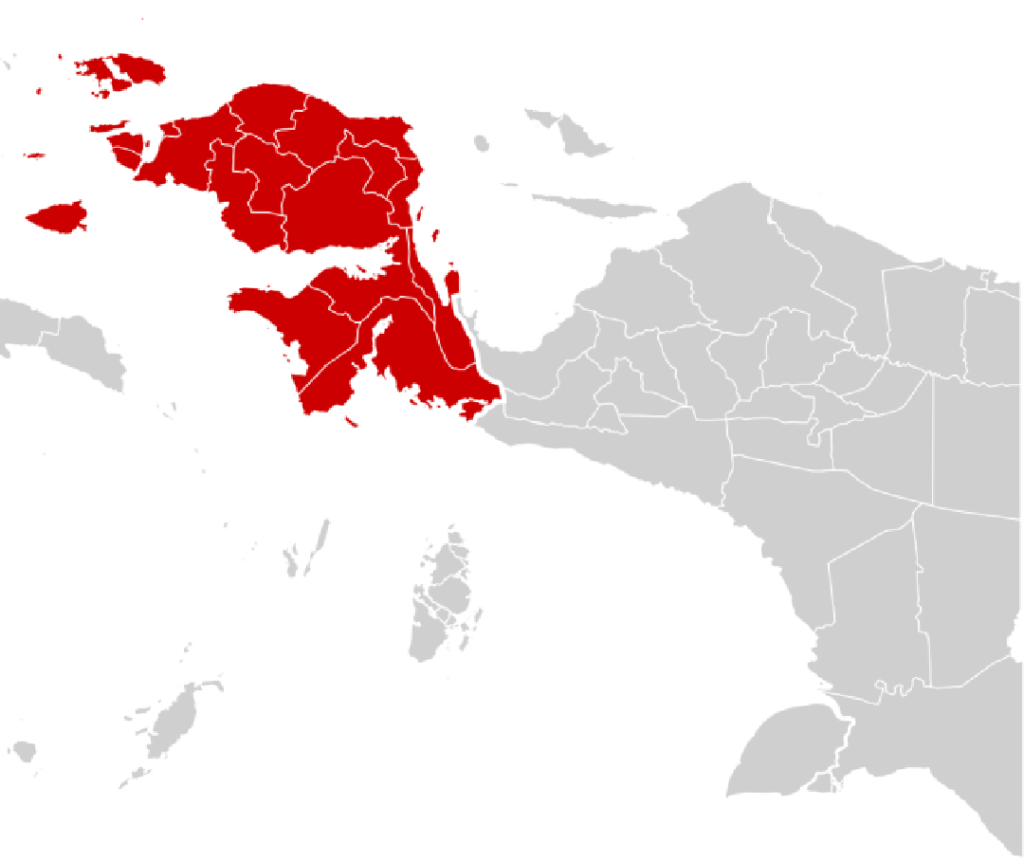

Papua has long been a land of beauty shadowed by conflict. Amid its towering mountains and vast rainforests lies a decades-long struggle between Indonesia’s security forces and separatist groups seeking independence. But in September 2025, the conflict took an unexpected international turn when two Australian nationals were arrested and charged with attempting to smuggle weapons into Papua. The weapons, investigators allege, were intended for the West Papua National Liberation Army-Papua Liberation Organization (TPNPB-OPM), the armed wing of the Free Papua Movement.

The revelation sent shockwaves across both Indonesia and Australia. It raised troubling questions about how far foreign actors are involved in sustaining Papua’s armed insurgency and what such involvement means for peace and stability in the region.

The Arrest That Shook Two Nations

Australian police confirmed the arrests after months of joint international investigation, which has been led by the Queensland Joint Counter-Terrorism Team, comprising the Australian Federal Police (AFP), Queensland Police Service (QPS), and the Australian Security Intelligence Organisation, working with New Zealand Police. The two men (JK and AAD) were arrested after authorities obtained a search warrant to raid their home in November 2024. There, Australian authorities claimed to have seized several items, including some illegal weapons and hundreds of bullets, explosives, and 13.6 kilograms of mercury metal. According to BBC Indonesia and Sindonews International, the men were accused of plotting to funnel firearms into Papua, strengthening the arsenal of TPNPB militants. Authorities linked the operation to ongoing clashes in West Papua, where insurgents regularly stage attacks against Indonesian soldiers, police, and even civilians.

The timing was particularly sensitive. The arrests came as the world’s attention remained fixed on the prolonged hostage crisis of New Zealand pilot Philip Mehrtens, who was abducted by TPNPB rebels in 2023. Although no evidence has confirmed a direct connection between the smuggling attempt and the hostage case, the coincidence fueled speculation that the two incidents may share common networks.

Yet the TPNPB quickly issued a denial. Spokesmen insisted they had never received weapons from Australians, accusing outside governments of “mixing up” the smuggling case with the Mehrtens kidnapping. The denials, published in outlets like Suara Papua and Odiyaiwuu.com, reflect the group’s awareness that any proven link to foreign gunrunners could erode its international sympathy.

Foreign Involvement in a Domestic Conflict

For Indonesia, the case exposed a deeper concern: the possibility of foreign nationals fueling domestic insurgency. While arms smuggling has been a known problem in Papua, the involvement of Australians—citizens of a close regional partner—hit particularly hard.

Australia has long reiterated its support for Indonesia’s territorial integrity. Officially, Canberra opposes Papuan independence and recognizes Papua as part of Indonesia. Yet the presence of its own citizens in a smuggling network undermines that stance, complicating bilateral relations at a sensitive moment.

“This is not just ordinary smuggling,” declared TB Hasanuddin, a retired major general of the Indonesian Army who now serves in the national parliament. Speaking to Tribunnews and Warta Kota, Hasanuddin stressed that the supply of weapons to separatist groups cannot be viewed as an isolated crime.

“It is a direct threat to Indonesia’s sovereignty. Each illegal weapon in Papua means more bloodshed, more attacks on our people, and more instability,” he said.

His words captured the sense of urgency. Illegal arms are not mere contraband; they are instruments that prolong violence, destabilize border regions, and complicate peacebuilding.

A Voice from Papua: Rejecting the Weapons

The revelations also sparked strong reactions within Papua itself. Ali Kabiay, a young Papuan leader often seen as a voice for moderation, openly condemned the involvement of foreign nationals. In an interview with Tribun Papua, Kabiay stressed that Papua does not need more guns; it needs opportunities and peace.

“Each new weapon smuggled into Papua means more widows, more orphans, and more broken families,” he said. “Foreigners who bring weapons are not helping us. They are making our lives worse.”

Kabiay’s statement resonated deeply with local communities. For many Papuans, daily life is already disrupted by violence. Villages are sometimes abandoned as clashes erupt between TPNPB fighters and Indonesian security forces. Farmers fear to work their land; children face uncertainty traveling to school. In this fragile environment, weapons smuggled from abroad do not represent freedom—they represent more suffering.

The Anatomy of Illegal Arms Trafficking

How do weapons even reach Papua? Experts note that the province’s geography makes it highly vulnerable. Surrounded by dense forests, rugged mountains, and vast coastlines, Papua is notoriously difficult to police. Its proximity to international waters also opens channels for smuggling.

Small arms can be hidden in fishing boats or commercial cargo. Money often flows through informal banking networks, making it hard to trace. And in some cases, regional crime syndicates exploit porous borders in Southeast Asia to move contraband, from narcotics to firearms.

Indonesia has made significant efforts to tighten border patrols, but gaps remain. The arrest of the two Australians may represent only one visible link in a much wider hidden network.

“This case is a reminder that illegal arms trafficking is not only a local problem but a transnational one,” Hasanuddin warned. “It requires cooperation between nations to dismantle these networks.”

Diplomacy Under Pressure

The arrests placed Australian authorities in a difficult position. On one hand, Canberra must prosecute the suspects vigorously to show that it will not tolerate its citizens undermining regional stability. On the other, the case risks being interpreted by some Papuan activists abroad as evidence of Australian sympathy for their cause—an image the government is keen to avoid.

Indonesian officials, meanwhile, are expected to push for stronger intelligence-sharing agreements. Maritime patrols in northern Australia and eastern Indonesia may need to be expanded. Law enforcement will likely focus more on financial flows and online marketplaces where illegal arms can be arranged.

Failure to act could create friction. If Indonesia perceives that foreign governments are not doing enough, it may strain diplomatic trust—at a time when regional cooperation is critical to navigating Indo-Pacific security challenges.

The Human Cost of Smuggled Guns

Beyond the headlines and courtroom drama lies the human cost. Each weapon that slips into Papua’s conflict zone can change countless lives. Security posts may be attacked; civilians may be caught in crossfire; communities may be displaced.

For villagers in Papua, the conflict is not an abstract geopolitical issue but an everyday fear. Mothers worry whether their children will return from school safely. Farmers hesitate before venturing to their fields. Traders fear traveling roads that could be ambushed by rebels.

That is why leaders like Ali Kabiay emphasize development over militarization. “Papua needs schools, hospitals, and jobs, not smuggled rifles,” he said firmly. His vision highlights a truth often lost in discussions of sovereignty and diplomacy: peace in Papua will ultimately depend on improving lives, not importing weapons.

TPNPB’s Strategic Messaging

The denials issued by TPNPB spokesmen also reflect the group’s evolving public relations strategy. By distancing itself from the smuggling case, TPNPB attempts to avoid being branded as dependent on foreign gunrunners. This matters because the group has long sought to present itself as a legitimate resistance movement, not a criminal organization.

Yet Indonesian security analysts caution that denials should not be taken at face value. Arms trafficking networks are designed to obscure their true beneficiaries. Even if the Australians did not hand over weapons directly to TPNPB leaders, they could still have been part of a chain that ultimately feeds insurgents.

Closing the Loopholes

As the trial of the Australian suspects unfolds, the case will test regional resolve. If convicted, the men could face lengthy prison sentences, sending a strong message that smuggling arms into conflict zones will not be tolerated.

But experts agree that trials alone will not solve the problem. To truly cut off the flow of weapons, Indonesia and its neighbors must address both the supply and demand sides of the equation. That means cracking down on international smuggling rings while also reducing the grievances that drive Papuans to pick up guns.

Development projects, better infrastructure, healthcare access, and educational opportunities are just as crucial as stronger border patrols. Without such efforts, the cycle of violence risks repeating endlessly.

Conclusion

The arrest of two Australian men accused of smuggling weapons to TPNPB-OPM has become more than a criminal case. It is a mirror reflecting the vulnerabilities of Papua, the dangers of illegal arms trafficking, and the risks of foreign involvement in Indonesia’s internal affairs.

Figures like TB Hasanuddin and Ali Kabiay have highlighted the stakes from different angles—Hasanuddin stressing national security, and Kabiay reminding us of the human cost. Together, their voices underline the urgency of stopping the flow of smuggled guns.

For Indonesia, Australia, and the wider Pacific region, the lesson is clear: peace in Papua cannot be imported with weapons. It must be built through cooperation, trust, and the creation of opportunities that give Papuans hope beyond the barrel of a gun.

Until then, every illegal shipment intercepted is not just a police victory—it is a small reprieve for the people of Papua, whose longing for peace remains as vast as their homeland’s mountains and seas.